−historical perspective−

Masayoshi NAKAWO (National Institutes for the Humanities)

Introduction

A vast arid and semi-arid region extends across central Eurasia, with annual precipitation of only several tens of millimetres in the lowlands where most people live. In the mountains surrounding the arid lowlands, however, annual precipitation is 400 to 800 mm, ten times greater than in the lowlands (e.g. Gao and Yang, 1985) There are many glaciers in the mountains, and their melt water contributes 10 to 50 % of the total discharge from the mountains (e.g. Ujihashi et al., 1998). Thus, a significant amount of water flows down from the mountains to the lowlands, and people depend on water, which comes from mountain regions, for farming or their daily life.

Fig. 1: Khara Khoto city buried with sand.

Water shortages became a big issue lately in the Heihe River basin, 38-43 degree N, 98-102 degree E, in western China. The underground water levels around the downstream area in particular have fallen dramatically. Wells that have always been in use before have suddenly run dry. Nearby vegetation is also on the verge of crisis. The Juyan Lake, the terminal lake, is also a shadow of its former self. These facts are major problems for the people who live in the lower reaches in particular.

There are many ruined cities, distributed in the downstream region of the basin, which have been abandoned, and buried with sands. No water is available at present around the relics of the cities as shown in Fig. 1. It is considered, however, that there must have been enough water for those people who used to live, when the cities were in prosperous. The water environment appears to have been changed significantly in the history, as Hoyanagi (1966) has speculated, with the help of many old documents, that climate change was mainly responsible on the decrease in river discharge from the mountains, causing the desiccation at and around the cities, examining many ruined cities buried in the central portion of the Taklamakan Desert.

The cause of the deterioration of the cities, or of the water environmental change has been examined in the Heihe River basin. The abandonment of the cities can be the result of the climate change, as Hoyanagi pointed out, but human activities may have played a major role, including the present water shortages.

Physical and historical settings

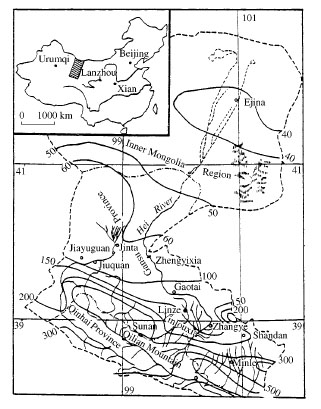

The Heihe River originates in the Qilian Mountains flows northward crossing the famous Silk Road, and terminates at terminal lake(s) (Fig.2). It is the second largest inner river in China. The area of the basin is about 130,000 km2, and it can be divided into three zones according to elevation. The upper reaches above 2500 m a.s.l. are the mountain zone with glaciers, where herdsmen of such minorities as Tibetans or Yogors keep their animals. In the middle reaches (2500-1200 m: oases zone), where annual precipitation is about 100 mm, and many Han people live, mostly in several oases, on irrigation agriculture. The lower reaches are below 1200 m (desert zone), where annual precipitation is below 50 mm. Mongolian people have long been keeping animals, but lately many Han people have migrated, started irrigation agriculture.

The Heihe River basin is located at what is historically the most important “cultural” crossroads where the Silk Road, in which cultures of the East and West meet, and some important trade routes, in which the different cultures of the North and South meet, converge.

Fig. 2: The Heihe Basin (revised from Wang and Cheng (1999)).

Contour lines are for the annual precipitation in mm/year.

Consequently, many ancient records, some over 2000 years old, called Juyuan Hanjian (Han Documents on Wooden strips) dating from the Han Dynasty have been unearthed from the region. Further, the mountain of documents at the old city of the Khara Khoto, which was in prosperous during Xixia and Yuan era, was discovered by the Russian explorer Colonel Pyotr K. Kozlov in 1907. Many more documents were discovered during the Khara Khoto (Black City) excavations by the Inner Mongolia Relic Archaeology Institute between 1983 and 1984. The Han script documents from among all these documents were finally published (Li, 1991). Many of these documents date from the era of Yuan rule.

2000 years ago, General Huo Qubing, who was in favour with the Han emperor Wu, marched his army north along the Heihe River to strike against the Hun (Xionnu) army in the Qilian Mountains. The nomads who make the Mongolian Steppes their base, in other cases, moved south along the Heihe River, also aiming for the Hexi Corridor, where the Silk Road is running through. If they were to continue south, they would pass over the Tibetan Plateau and eventually reach far-off Yunnan. In other words, the Heihe River acts as an intersection on the main north/south trunk road that crosses the Silk Road, which runs east/west. Calling this a node on the major roads running north/south and east/west can only be because it is militarily important.

Emperor Wu, who captured the Hexi Corridor from the Huns, embarked on managing the western territories by setting up the Hexi districts in 121 BC. There were four Hexi districts. In order from the east these were Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan, and Dunghuang. As well as setting up a military base, he also built numerous beacons along the Heihe River.

At the same time, he stationed many colonial troops there as a bulwark against the Huns to the north. In peacetime, it is thought that they drew water from the Heihe River and engaged in irrigation farming. There were not only the so-called colonial troops, but also numerous regular colonists engaged in farming (Momiyama, 1999). Their numbers reached 1.3 million according to the records alone (Nakawo, 2009). The population was in the same order of magnitude as today, since the present population is around 1.8 million.

Passing down the years, we come to the Xixia Dynasty. The Xixia was a country mostly of Tangut people centered on Xingquingfu (Yinchuan at present, which is in an autonomous region of the Ningxia Huizu people) between the 11th and 13th centuries. At the height of its prosperity, these people governed the Hexi Corridor, and built the Khara Khoto in Juyan, downstream of the basin. The region stretched approximately 20 km southeast from the current Ejina Oasis. The Khara Khoto at the time was the front line of the Xixia military, where they confronted the Mongol armies, who later founded the Yuan Dynasty.

The Xixia surrendered to the Mongol armies in 1227. Thereafter, the Mongols became the great Yuan states, and metamorphosed into the first global empire in human history. As a matter of course, the role of the Khara Khoto as a military front line disappeared. Instead, the Khara Khoto, was expanded by almost a fourfold scale compared to during the Xixia Dynasty, and flourished as a core trading city. They developed again the farmland very intensively to be self sufficient to feed the people of the basin, who accounted for roughly 2 million people (Nakawo, 2009), more than the present population.

The Khara Khoto rule by the Yuan also signaled the end due to invasion by the Ming. Consequently, the population of the Khara Khoto region, which corresponds to the most downstream point of the Heihe River (i.e., the area around the modern-day Ejina Oasis) can be presumed to have fallen sharply. The Ming abandoned rule in the region, and established instead a site for implementing their rule at the southern end of the long wall that they built along the northern boundary of modern-day Gansu Province. It is thought that there were a considerable number of nomads around the Khara Khoto as always, but at that time the Khara Khoto itself was abandoned, and gradually came to be buried under the sands.

During the Qing Dynasty, the Mongolian nomads called Torγuud returned from Russia to China, and started to live in the vicinity of the downstream Ejina Oasis with the permission of the Qing Dynasty. Almost 300 years have passed since they settled down. At the start of the 20th century, approximately 10,000 people were living there, and lately the population has been doubled, after the rule of the People’s Republic of China, with the migration of Han people.

Reconstruction of the past water environment

There is a small lake called Tien-e-hu (Swan Lake), which is less than a kilometer in diameter (Fig. 3), at the eastern side of Ejina Oasis. Endo et al. (2003) found concentrically lined array of gravels surrounding the lake, being roughly parallel to the shoreline of the lake. The gravel bars indicated the past shore lines of the lake, and AMS dating of spiral shells found under every bars provided the past changes of the shore line, and the past lake sizes for respective era. The lake was as large as 1800 km2 before 2000 years BP, during Han era, and it is identical with the Old Juyan Lake appeared in old documents. The lake started decreasing towards the end of Han era.

Fig. 3: Lake Tien-e-hu at present.

We can imagine the scale of the old lake with the topography.

Endo et al. (2007) found also that the river channel migrated to northward, and commenced to form present Ejina Oasis, based on the result that the bottom of the lake sediment of Gashon-nur, located at the north of Ejina, was dated at around 1200 AD, by AMS. They considered that the migration of the river channel was caused by a sand dune deposition on the previous channel, i.e. natural cause. Jin (2000) claimed, however, that the channel migration is to be attributed to the tactics of armies either of the Yuan or the Ming, who attacked the Khara Khoto, making an artificial dam in order to prevent the water flow to the city, i.e. human cause. The Xixia surrendered to the Mongol armies in 1227, and the Mongol surrendered to the Ming at 1372, and the AMS dating is not precise enough to distinguish between the two. We are not sure at the moment, however, if the change in river course is by natural or artificial, since the investigation at the diverging point of the old and new channels, where Chinese military base is presently located, is not allowed for foreign researchers.

There are many relics of old irrigation canals in the lower reaches of the Heihe River, of which some are enclosing the Khara Khoto, as old maps show. Sohma et al. (2007) tried to estimate the distribution of farmland in Han and Xixia/Yuan eras (Fig. 4), spreading at the vicinity of the canals, by stereoscopic examination of the CORONA satellite pictures, and the in situ investigations. As the results, it was found that the farmland was approximately 120 km2 and 110 km2 in Han and Xixia/Yuan eras respectively (Moriya, 2011), when the population was in the same order of magnitude as present. The farmland areas are almost equivalent with the area of agricultural land at present. So the water consumption for irrigation agriculture was in the two eras.

Fig. 4: Old farmland in Xixia/Yuan eras along the old irrigation canal.

Sakai (2011) reconstructed the river discharge from the Qilian Mountains for the last 2000 years, by using reconstructed past temperatures by Yang et al. (2002) and precipitation by Zhang et al. (2003), with the help of a hydrological model combined with a glacier mass balance model (Sakai, 2009). It was found that the water supply from the mountains is rather stable during Han era toward the 4th Century, although the water volume was smaller than the present discharge.

The calculated values for variations in water flow largely depend upon precipitation data reconstructed. Due to the fact that rainfall was estimated from the annual tree ring index, and hence the calculating errors in water flow also depend on the annual tree index. The annual tree ring index uses things like wooden coffins and buildings prior to 1200 AD, and the calculating errors should be large in determining the year of a particular tree prior to 1200 AD. It is considered, therefore, that post-1200AD water flow data are comparatively reliable.

The fluctuation of discharge data after 1200 AD is hence compared with historical documents available which indicate water shortages in the basin, among which the following six periods stand out in the period after 1200 AD:

- A. 1250 -1300

- B. 1449 - 1520

- C. 1531 - 1556

- D. 1717 - 1721

- E. 1749 - 1772

- F. 1928 − 1939

Discussion

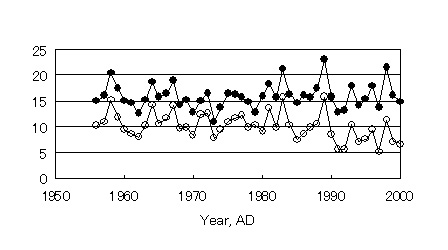

We have examined the cause of the recent water shortages as well (Nakawo, 2009). The volume of water from the mountains has been rather stable, in the last 50 years, although warming is significant. It seems that an acceleration of glacier melt could have offset a gradual decrease in precipitation, owing to the warming. The river discharge from the middle reaches to the lower reaches, however, has declined very rapidly, roughly by two third in the 50 years, which caused the severe water shortages in downstream (Fig. 5). The recent water shortage is considered, therefore, to result mainly from an overuse of water in the oases zone (middle reaches).

Fig. 5: The change in rate of river discharge (unit: m3/s).

Solid circles indicate the discharge at a station between the upper and middle reaches, and open circles at a station between the middle and lower reaches. (after Nakawo (2009))

In order to cope with the water shortages, two countermeasures have been established: a limit to the river water drawn midstream, and reforestation. The amount of water flowing downstream has increased due to the limits on water drawing, but farmers at the oases, where the amount of water drawn has been reduced, have compensated for the insufficiencies by digging wells and using aquifers to maintain their farmlands. For reforestation, a policy of “ecological migration” has been adopted, whereby shepherds from the foothills are made to migrate to nearer the oases (Nakawo et al, 2010). These transplanted herders, however, have started to develop farmlands to feed their animals. In other words, more oasis water is needed than ever, and the shallow wells have started to dry up even as far as midstream Zhangye. To compensate, an abundance of deep wells have been dug.

A rapid shrinkage of Old Juyan Lake during Han era is also considered as one of the results of the rapid agricultural development by the Han colonial troops, since the discharge from the mountains was rather stable, having not been changed dramatically. Cooling trend was found in the period of Xixia to Yuan eras (Yang et al, 2002), and accordingly significant decrease of discharge from the mountains took place (Sakai, 2011). In this period, however, cultivation was very intensive by making new irrigation canals in the middle reaches in particular, in addition to the farming in the lower reaches with the area equivalent with the cultivation in Han era or at present. It is considered, therefore, that the water shortages in A period are led by the synergism of climate change and human cultivation.

We have no data on agricultural development in B, D and F periods in Ming and Qing eras, but it would be reasonable that the water shortages in these periods are caused mainly by the human activities, although the shortages could have been caused by climate change in C and E periods.

One old document of petition sent to the local government in the middle reaches, written in 1726 in Qing era, mentions that “Water does not come from spring to summer to the lower reaches, due to the water consumption in middle reaches. We can use only pond water left in the river bed!” (Inoue, 2007). The situation was completely the same as today, although a severe drought was not recorded in this particular year. It certainly indicates that agricultural use of water caused the water shortages in the lower reaches, and that they have realized the cause at that time.

It is considered, therefore, that water shortages in the Heihe River basin seem to have taken place intermittently in the history, owing to the people’s activities in many cases, although the climate change is responsible in some cases.

Concluding remarks

The arid areas have an abundance of sunlight. Provided there is water, the location is perfect for plant husbandry. In the dry areas of the central Eurasian continent, firstly, people create products to support themselves using the riverbanks and spring waters. Before long, provided there is water, they think they can create even more products, and so have built an irrigation system. Further, they want more water, and have brought it from afar to change a wider area into farmland. Through repeating this process, they have used so much water that the river water downstream has ceased flowing.

When the river water became insufficient, they decided to use the aquifers, and dug the wells. The well water proved convenient, so they used it without restraint. The aquifer levels fell, and the shallow wells dried up. Whereupon, they started to use the deep aquifers. This is the present situation in the Heihe River basin.

Due to the recent warming, the glaciers may disappear within 100 years, and there is a great possibility that the river flow will be reduced rapidly. Conversely, even if there is a cold spell, the river flow will also fall. The glaciers will grow, and the river water will be reduced by that amount. In either case, it is likely that the waters of the Heihe River will fall in the future. It is necessary to consider these implications for the future. Climate change affects people’s life significantly worldwide. Since water, the most valuable substance, are mostly supplied from the mountains in arid areas in central Eurasia. Climate change in the mountains would affect very much the water supply to the lowland where many people stay. Climate change is hence very important. As we have discussed above, however, drought conditions in people’s life are not just by the amount of water supply from the mountains, but also by how people would utilize those water, or how to distribute to what. When we considered how to cope with the water shortages or other environmental issues, therefore, we have to examine both natural systems and human activities at the same time. In other words, integrated researches are necessary examining both in highland and lowland, and both on natural changes and human actions.

Acknowledgements

This is a contribution from the Oasis Project promoted by the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all members of the project for their fruitful contributions to the project. The study is partly supported financially by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 19201005) of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

Endo K, Sohma H, Mu G, Hori K, Murata T, Qi W. 2003, Reconstruction of paleoenvironments in the lower reaches of Heihe and Juyan lake area −migration of river course and Juyan lakes-. Project Report on an Oasis-region, Research Team for the Oasis Project, Research Institutes for Humanity and Nature, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1-10.

Endo K, Qi W, Mu G, Zheng X, Murata T, Hori K, Sohma H, Takada M. 2007, Change of desert environment and human activities during the last 3000 years in the lowest reaches of heihe River, China. [in Japanese with English abstract], Project Report on an Oasis-region, Research Team for the Oasis Project, Research Institutes for Humanity and Nature, Vol. 6, No. 2, 181-199.

Gao Q, Yang X. 1991. Discharge characteristics and glacial input of inner rivers in Hexi corridor, Gansu. [in Chinese], Lanzhou Institute of Glaciology and Geocryology, No. 5, 131-141.

Hoyanagi M, 1966, Geographical problems concerning the Old Silk Road region in the Tarim Basin. Geographical Report of Tokyo Metropolitan University, No. 1, 1-32.

Inoue M. 2007, On the interruption and the distribution rule of the Heihe river water at the Yongzheng era, Qing dynasty [in Japanese with English abstract]. In: Inoue M, Kato Y, Moriya K. editors. Collected papers on the history of oases region −description of the 2000 years in the Heihe Basin-. Shoukado.

Jin A, 2000, General view on desert archaeology. [in Chinese], Zijincheng Chubanshe.

Li Y. 1991, Documents Excavated at Khara Khoto, [in Chinese], Kexue Chubanshe. Momiyama A. 1999, Han Empire and the remote region [in Japanese]. Chuokoronsha Inc.

Moriya K. 2011, From the Western Han Dynasty to the Five Liangs Period [in Japanese]. In: Nakawo M. editor. History and Environment in an oasis region, Bensei Publishing Inc., 11-48.

Nakawo M. 2009, Water shortage in an oasis region in western China. In: Abe K, Nickum JE editors, Good Earths, Regional and Historical Insights into China’s Environment, Kyoto University Press, 173-181.

Nakawo M, Konagaya Y, Shinjilt editors, 2010, Ecological Migration −Environmental Policy in China-. Peter Lang, pp. 283.

Sakai A. Fujita K, Nakawo M, Yao T. 2009, Simplification of heat balance calculation and its application to the glacier runoff from the July 1st Glacier in northwest China since 1930s. Hydrological Processes, 23, 585-596. Sakai A. 2011, Fluctuations in the black water from the mountains of heaven [in Japanese]. In: Nakawo M editor. History and Environment in an oasis region, Bensei Publishing Inc., 107-115.

Sohma H, Mu G, Qi W, Hori K, Kato Y, Moriya K. 2007, Relics and the environmental change in the lower reaches of the Heihe River [in Japanese with English abstract] . Project Report on an Oasis-region, Research Team for the Oasis Project, Research Institutes for Humanity and Nature, Vol. 6, No. 2, 107-121.

Ujihashi Y, Liu J, Nakawo M. 1998. The contribution of glacier melt to the river discharge in an arid region. Proceedings of the International Conference on Ecology of High Mountain Areas, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 413-422.

Wang G, Cheng G 1999. Water resource development and its influence on the environment in arid areas of China −the case of the Hei River basin. Journal of arid environments, Vol. 43, 121-131.

Yang B, Braeuning A, Johnson KR, Shi YF. 2002. General characteristics of temperature variation in China during the last two millennia. Geophys. Res. Letters, 29(9), 1324, doi: 10.1029/2001GL014485.

Zhang QB, Cheng G, Yao T, Kang X, Huang J. 2003. A 2,326-year tree-ring record of climate variability on the northern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Letters, 30(14), 1739, doi: 10.1029/2003GL017425.

(Invited presentation at the International Symposium on theGlobal Change and the World's Mountains, at Perth, Scotland in September, 2010.)